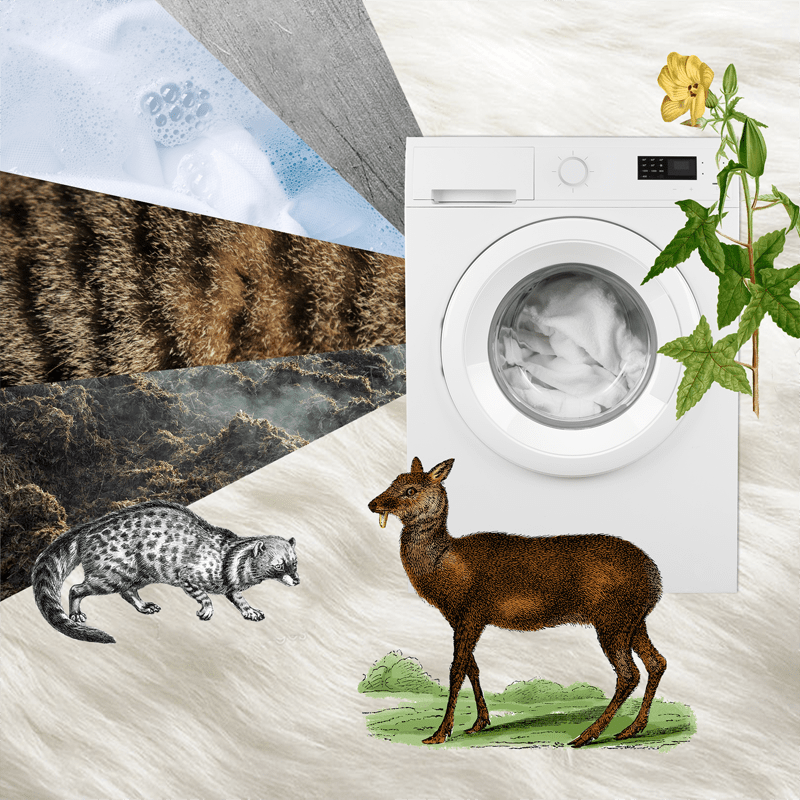

The scent of cotton. It is, arguably, a “fantasy note” in perfumery terms, as cotton is not distilled or made into an aromatic material, nor does it have much of a scent at all. But when I stick my nose into these fluffs of raw cotton, there is a texture that comes through in the way of smell: soft, swaddling comfort, muffled and peacefully quiet, enveloping like a clean cocoon. “Fantasy notes” use smell in non-literal ways to evoke ambiance, moods, associations, and ideas—which is why it’s such a powerful choice that Bright Black Candles and Cocoasavvy included the textural scent of cotton in these two beautiful candles. The history of cotton—and the wealth and economic power that the US gained through it—is inextricable from the history of slavery, sharecropping, injustice, and the dehumanization of Black lives.

“So much of Bright Black is about seizing control of our narratives and reclaiming our history as a means of shaping the present and the future,” write Tiffany and Dariel of @brightblackcandle in a post about the Durham candle from their Diaspora collection. “This is why we blended cotton with our other fragrance notes in our Durham scent. We were inspired by @blackcotton.us and their movement to position cotton positively (which is a very different framing than we grew up with in the North). From a scent perspective, the cotton softens the whiskey and tobacco notes, rounding it out and providing balance to what would have otherwise been quite a harsh aroma.” The smell is rich, sultry, enveloping, and deep.

For Alita Carter’s @cocoasavvy brand, Bright Black created a scent using notes of cotton, cocoa, and sugar cane—all three major cash crops produced in the Americas, all three produced largely by Black and African people, some free, many not. In Tiffany and Dariel’s words, this candle is in many ways “a tribute to the Americas and the contributions so many Black people provided to growth in these regions….It’s a tender scent, a consoling scent, an almost mitigating scent—sending reassuring messages that tomorrow will be ok, even if today is tough. That hopefulness flows all through this candle, and has flowed throughout our history in North, South, and Central America (and throughout the entire Diaspora really).” Alita paired the scent with Margaret Walker’s poem “For My People.” “…For my people standing staring trying to fashion a better way / from confusion, from hypocrisy and misunderstanding, / trying to fashion a world that will hold all the people, / all the faces, all the adams and eves and their countless generations; // Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born….”

The Cocoasavvy candle can be purchased at cocoasavvy.com, and the Durham candle can be purchased at brightblackcandles.com. The raw cotton bouquet pictured above is from blackcotton.us, a family farm and community-focused company in North Carolina. Give them a follow and take a look at what they’re doing to strengthen their community through agriculture.